How to Stop Wasting Money on Characterization Programs

By: Jason FlatteryWhen I work with consultants, they often tell me they know exactly what they want to achieve with their investigation program budget. After I ask some questions, however, it becomes clear the plan is not defined well enough to respond to pricing requests. It’s important to take a step out of the current pushing us into the next phase of the investigation. In this blog post, I’ll cover how we can do that.

If you'd like to dive a little deeper, join me next week for my webinar, How to Design an Efficient HRSC Program Based on Objectives and Data Gaps. I'll be taking questions during the Q&A, so be sure to submit yours during registration.

As a former consultant, I understand how easy it is to overlook options or questions that seem obvious in hindsight—I’ve been guilty of it myself. Maybe the site is one you’ve been working on for years and has developed a sense of “momentum,” or it’s a new site that seems small and simple. It can seem obvious, for example, that we need a new pair of monitoring wells to fill a spatial gap in the existing well network, or it can feel like grabbing a day’s worth of soil samples from a direct push rig is all we need to move this new site along. But time and again, this approach wastes money and does not put you in a position to succeed for your client.

Let’s explore the monitoring well example from above. The objective of that investigation was to fill a data gap in an existing well network. It seemed straightforward and easy enough. Your client was expecting you to propose to put in more wells, so the budget was easy to secure. For a few thousand dollars in installation costs, two days in the field to install the wells, some waiting period for well equilibration following development, another field mobilization to sample the wells, another week or two to get results back from the laboratory, etc. you get your answers. But wait…

Was the existing well network even installed in the right places in the first place?

Does it matter if we fill in the data gaps in that well network?

Could we use that budget ($5,000? $10,000?) and calendar time (a month maybe?) to move the site closer to closure than just by putting in two new wells?

Did anyone ask these questions before it was too late?

Now you might find yourself explaining to your client why you need more data (and money) to explain an anomalous concentration trend in the well data, or that the source area is not understood well enough to design a successful remediation program.

No one wants to end up in that situation. As both a consultant and now a contractor, I’ve learned there are no shortcuts to the process if we want to be effective and efficient with our characterization budget. Here’s the three-step process we need to use to ensure success:

1. DEFINE THE GOALS OF THE INVESTIGATION

Get the project team together and talk through this step. Using design thinking can be a great way to structure this conversation and strip it down to the actual objective. Depending on the dynamic between you and your client, you might even include them in the conversation.

Ask questions. All questions are good questions, especially “why?”

For the monitoring wells example, the evolution might be:

Objective Iteration No. 1: “We need to fill in the data gaps in the monitoring well network by installing two new wells at the toe of the plume.”

Responses: Why do we need to fill those data gaps? Is there expected to be significant mass there or are we approaching a potential receptor? Did someone require wells in those locations?

Objective Iteration 2: Those wells are needed to complete the delineation of impacts above the drinking water standard required by the regulations. So, “We are completing the delineation of groundwater impacts above the drinking water standard required by regulations.”

This is a real objective. It is clear and concise and can be used to design a solution. The discussion can now move onto step two.

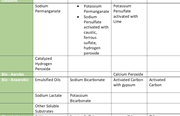

2. SELECT TOOLS AND METHODS

Here you can consider all alternatives, not just the solution you may have had in mind when you approached the table. The important part is that you have the option now to address the wider issue and not just the problem that was immediately in front you before.

Back to our example:

You might look at how the well network as a whole is solving your delineation problem. Other than those farthest downgradient data gaps, do you have clean compliance data on the sides of the plume? Do you have the vertical bounding necessary to meet the requirements? How do you know how far downgradient the next set of wells should go? How will you ensure the screens are placed at the correct depths?

Here you can consider an HRSC approach. You might not just focus on those downgradient points. On this same mobilization, it now becomes cost effective to collect missing source area data, confirm the horizontal and vertical extents of the plume within the area of the existing well network, and ensure you place the new downgradient wells in the correct locations and at the correct depths. Will you operate the investigation dynamically, using the real-time data set to select the location of the next boring? What are your constraints (think operator site access, topography, utility clearance protocols, etc.)? Once you have walked through these questions, it’s time to move on to step three.

3. DEFINE THE INVESTIGATION LOCATIONS AND DEPTHS (FINALLY)

Here’s the step that we’re often inclined to jump to first. But look where we are in our example: originally, we were discussing where to place the screens on two new monitoring wells, with the best possible outcome being that we guessed correctly and made a potentially inefficient well network complete. With that approach, that is all you’d get—no other benefits would be achieved, and you likely would not have completed the delineation.

Instead, we might be discussing a 30-location membrane interface probe-hydraulic profiling tool (MIHPT) program. This option would define exactly where those two wells should be constructed, while also confirming clean horizontal and vertical boundaries throughout the plume, and providing information about source area architecture that can be used to properly vet remedial options and designs. This approach can achieve the true program goal of completing the delineation, while providing additional value for the upcoming remediation phase.

During this step, you need to determine how best to use your budget to move as far as possible toward closure. If you decided on a phased approach or a dynamic strategy, you would need to place primary locations and secondary, or step-out, locations on your site plan. This could be a grid laid upon a suspected fuel oil release, or a set of transects laid cross-gradient along a solvents plume.

This step is also where most of us reach out to contractors for quotes. But as a consultant-turned-contractor, my goal is to make sure I understand your overall objectives instead of immediately firing back pricing—this ensures I’m on the same page and can help you get the most bang for your characterization buck. And it might help you see your project with refreshed eyes—and a clearer picture of the goal you’re aiming for.

If you'd like to learn more, register for next week's webinar, How to Design an Efficient HRSC Program Based on Objectives and Data Gaps. A link to the recording will be sent to those who can't attend, so RSVP either way.

My team and I would be happy to discuss your site in detail and provide some feedback and suggestions on any of these steps. We can work together to make sure you are the last consultant to work on this site.